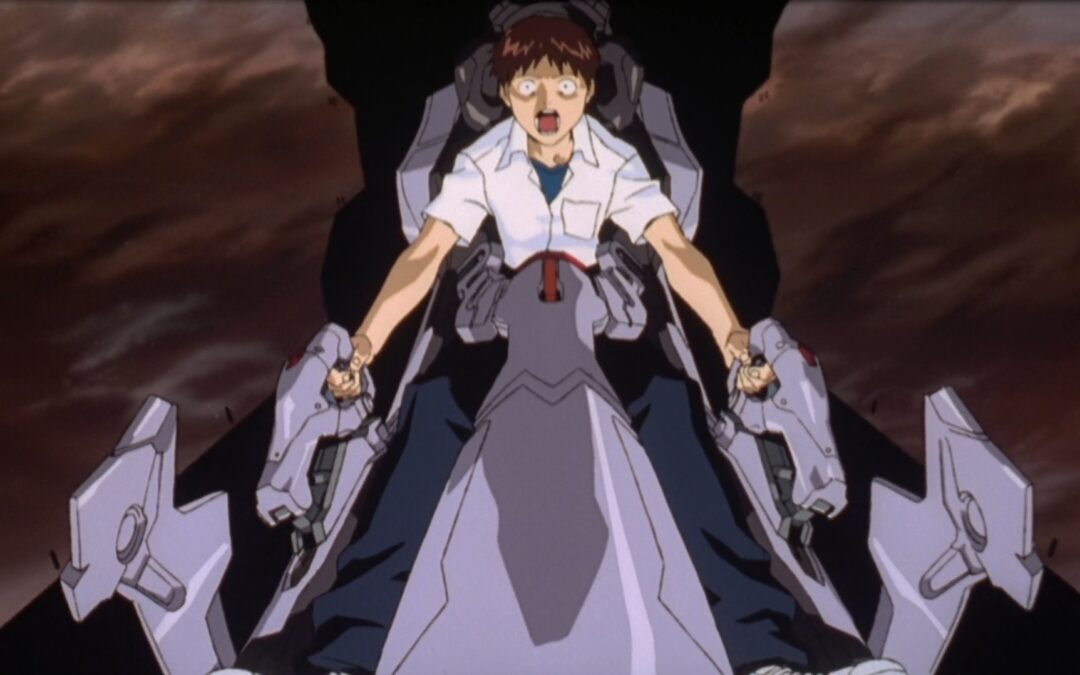

Most of Evangelion ’s good reputation in the non-Japanese fandom comes from its status as a “deconstruction”. Evangelion is much more character focused, but only in the specific sense that it is more individualistic and that it is the characters that set the tone of the story, rather than the opposite. Just as Asuka’s introduction changed the tone of the show, it is Shinji’s breakdown in episode 16 that provokes the second tone shift. Ideon‘s characters are tortured and psychologically challenged, but the show is not just that, whereas in Evangelion, the entirety of the storytelling is progressively invaded by the psychology of the characters. This is why Evangelion did feel original, and did renew anime as a whole: it’s not that it introduced psychological nuance, as it was always there, but rather that it gave it a role such an important role. The focus of Evangelion is therefore first and foremost the individual, and the apocalypse is as much a cool SF setting as a metaphor for the character’s troubled psychology.

#EVANGELION EPISODE 4 RYU SERIES#

In Evangelion, the entire world is at stake but the series ends, both in the original and movie, just on the main characters, and especially on Shinji’s psyche. On the other hand, Anno’s series, and more generally a Gainax’s work (see Wings of Honneamise) had always had a more individualistic focus. Tomino had always been preoccupied with collective issues, as the political themes present thoughout his work illustrate. Although both Ideon and Evangelion share an almost cosmical scale, the way they show it is very different. It’s in fact at the core of Anno and Tomino’s relationship, and what makes them different.

Evangelion doesn’t go that far, which is maybe not surprising when you consider that Gainax’s staff is generally less left-leaning than Tomino and his team always were.īut this difference isn’t just due to politics. Specific, because it illustrates its point through the exploration of two real-world political issues: racism and militarism. In its exploration of it, Ideon is more specific and pessimistic. At their core, both shows are about the impossibility of human communication – a recurring theme throughout Tomino’s work that Anno would make his.

#EVANGELION EPISODE 4 RYU TV#

This is true, but let’s not forget that this moment is also meant to be fun: we’re meant to laugh at Shinji’s awkwardness as he holds his breath and can’t kiss Asuka properly.Īs for the TV series, Evangelion borrowed some narrative elements, but what’s most interesting is how it also took many of the thematic elements that go with them. In retrospect, once you’re done or have reflected on the show, this scene will appear as a sad moment, yet another failure in the communication between the characters. It is also there that the show goes the furthest in the romance department, with the pathetic but most of all comedic kissing scene from episode 15. It is mostly about the main trio of pilots and their interactions.

This middle part of the show maintains the mysterious, sometimes dark atmosphere of the rest, but its focus is different. It contains some of the most improbable scenarios (such as the combined attack of Units 1 and 2 in episode 9) as well as some of the most fun and/or annoying interactions between the members of the cast (episodes 10-11). Then, until episodes 15-16, the show adopts a classical monster of the week format, directly taken from tokusatsu series and mecha anime. But even then, Nadesico is a quintessentially otaku work, with its harem, Getter Robo references and cool robots. On the other hand, Nadesico clearly diagnoses violence and militarism as features of its own genre and tries to offer a way out from those trappings. These are features of the world, and even if this wasn’t a mecha show, these things would still exist: the show’s abundant use of psychoanalysis makes clear these are universal issues. Evangelion shows brutality, violence and abuse, but never explicitly criticizes them as a part of its generic codes. Although Evangelion did it with a much darker tone, a parallel with Nadesico is quite instructive. Both shows directly addressed (much more directly than Evangelion ) the collusions between nationalism/militarism and Japanese science fiction, especially in an otaku context. And, just after Evangelion, there was Martian Successor Nadesico in 1996. The most notable one before Evangelion was Irresponsible Captain Tylor in 1993, with its gentle jabs at the space opera genre. Or, rather than deconstruction, parodies. As for shows aimed more specifically at otaku, deconstruction was getting trendy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)